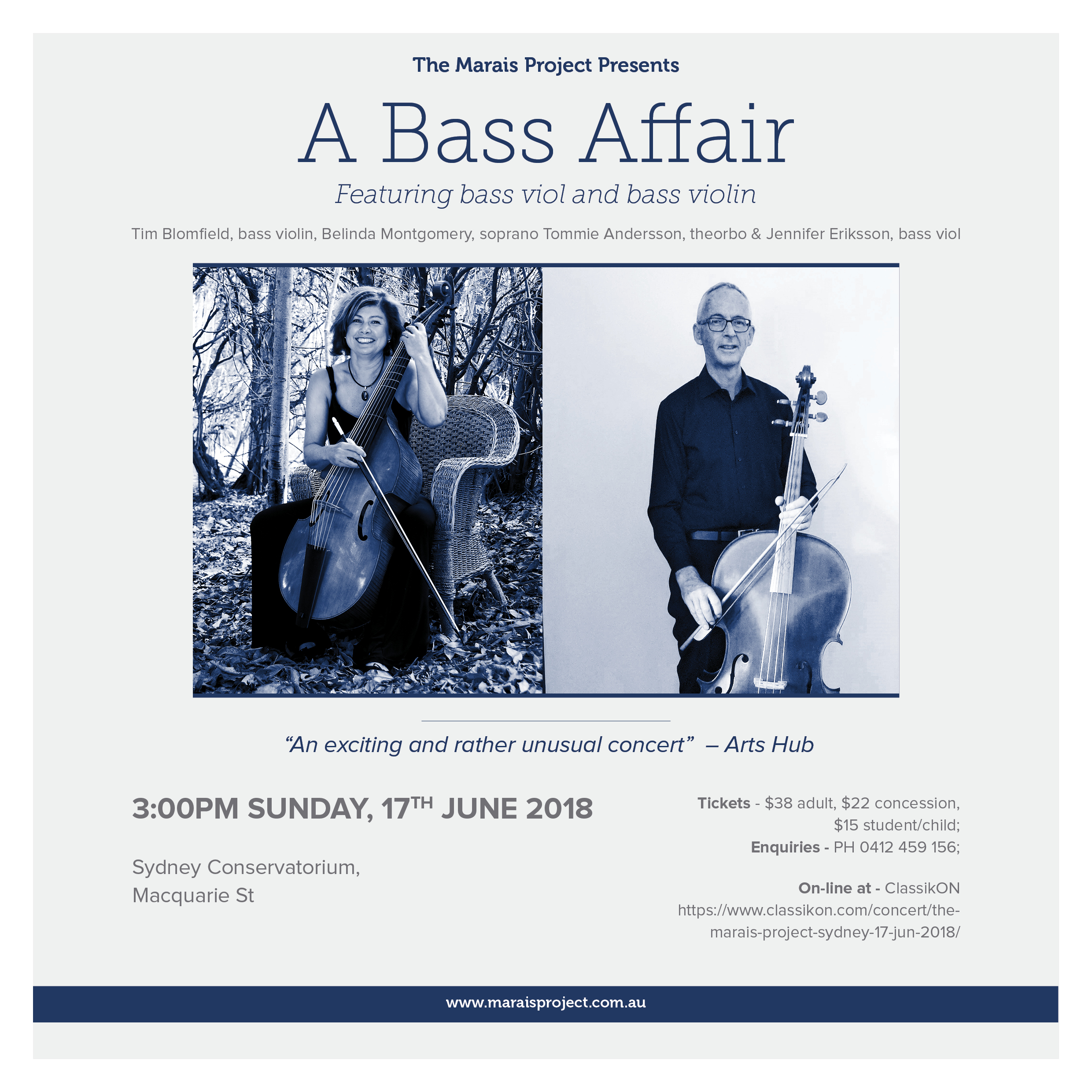

Featuring Bass Viol and Bass Violin

What: The Marais Project with bass violinist, Tim Blomfield

When: 3.00pm June 17, 2018

Where: Sydney Conservatorium of Music, Macquarie St, Sydney

Cost: $38 $22 and $15

Tickets: https://www.classikon.com/concert/the-marais-project-sydney-17-jun-2018/

Contact: Philip Pogson 0412 459 156; philippogson@theleadingpartnership.com.au

———————————————-

Most early music fans are aware that the viola da gamba is also known as the bass viol. It is less well known, perhaps, that there is also such an instrument as the bass violin, also known as the ‘basse de violon’. The bass viol and bass violin were mainstays in French baroque music and featured in the Court orchestra of King Louis XIV. For this concert The Marais Project welcomes Tim Blomfield, one of Australia’s finest bass violinists and co-founder of Sydney’s long standing and highly respected early music ensemble, Salut! Baroque. Tim talks to Philip Pogson.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Philip Pogson (PP) – Tim what are you looking forward to in performing with The Marais Project on 17 June?

Tim Blomfield (TB) – I look forward to again collaborating with my very good friend, Jennifer Eriksson, and having the opportunity of both directly juxtaposing and blending the basse de violon with its quintessential French partner, the basse de viole. It will be a wonderful opportunity to display something to an audience, the majority of which would never have had that experience.

PP – Going back in time, what was behind your decision to move from the modern to the baroque cello?

TB – Ever since I was young, I was attracted to baroque music. Learning the piano from the age of 5, it eventually dawned on me that the piano (as I knew it then) was a post-baroque instrument and could never represent music from that era with any integrity. Ultimately, my piano teacher Josephine Bell conceded that to be the case, very admirable for the likes of her! But as it was the piano that she was teaching me to play, not the harpsichord, we (resentfully) carried on regardless. At least I had won a small victory by her free admission, albeit that I was still troubled by hearing the “wrong” sounds as I played keyboard music, on the piano, by 17th and 18th century composers.

For example, one day before school, I was practising the Gigue from JS Bach’s French Suite №3 in B Minor BWV 814. In one bar, there was a constant clash – a jarring of sounds. I was totally perplexed. I was already in awe of JSB, yet I couldn’t get my head around how or why he would have written such a series of discords. It was only years later, playing the same piece on a harpsichord that my sensibilities were relieved, and my total belief in the master was reconciled – because at last I was playing the piece on the harpsichord where the discords melted away into unaccented passing notes, not accented ones, as they always became on the piano! Playing baroque music on modern day equivalents of baroque instruments was never going to “do it” for me. Music could only ever have its integrity when played on instruments of which the composer was aware.

My story regarding the cello, which I began learning in Year 7, has similarities. My AMEB Musicianship teacher had a son who played the recorder. Being a pianist with an interest in things baroque, she bought a Zuckerman kit harpsichord. By this time, I was aware of the cello’s fundamental role in the baroque era being an instrument that supported the bassline. “Mrs Ward” must have been aware of my awareness as, during one school summer holiday period, she invited me to come and play basso continuo with her son. He played the recorder while she played the harpsichord. On the menu were GF Händel recorder sonatas. Although I had no awareness of the baroque cello at that time, something felt incredibly “right” about me performing this role in this context.

The year was 1975 and I was sold on this sound-world … forever. Fast forward another few years: in 1980 I found myself (ultimately, incredibly fortuitously) at the Sydney Conservatorium in Howard Oberg’s Diploma of Music Education (compulsory) recorder class. In those early weeks, Howard knew nothing of any of his Music Education students’ musical penchants but once he discovered whatever anyone’s instrument happened to be, he would immediately boldly pronounce, “Oh then, you should play the [substitute whichever the baroque equivalent was of what that student was studying as their major study]. So, in my case, it was, “Oh then, Tim, you SHOULD PLAY the BAROQUE cello!” My heart Jumped arrhythmically; here was a man who had my very sympathies at heart, although to what extent he could not yet have known. The rest, as they say is (Baroque) History …

PP – You spent several years doing post graduate studies on baroque cello in Holland. How did that time overseas impact you?

TB – With the benefit of hindsight I can now see that through a combination of factors, including my ambivalence with being a modern cellist, poor teaching and a lack of down-to-earth guidance, I was never going to make it as a modern cellist. I could sense, however, that if I followed my heart I could make a clean break, rise from where I was and make a fresh start – with the baroque cello.

In 1983 I procured luthier John (Ben) Hall’s initial foray into baroque cello manufacture. As I remember, Ben also made Jenny Eriksson’s first viola da gamba. Later, in Holland, I was thrilled by my teacher Jaap ter Linden’s pronouncement that, “This cello (by John Hall) is arguably the best replica of a genuine baroque cello that I have yet seen or heard”. That opinion was later seconded by Wieland Kuijken’s admiration, “Such a wonderful instrument it is!”. My confidence received an immediate boost.

Thanks also to the immeasurable quantity of guidance and experience that I received from Howard Oberg, through the opportunities he offered me in providing hours of bassline support for his recorder and baroque flute students, by the time I arrived in Holland I was ahead of my colleagues in knowing how to play a supportive bass.

Within just a couple of weeks of taking up residence in The Hague, the phone started ringing with requests for me to accompany this student or that, or to deputise for someone at such and such a rehearsal, though none of the callers had yet met me nor heard me playing basso continuo. These being the days before social media had been concocted – through social media anyone can now quickly discover an individual’s past reputation – it soon dawned on me that I could totally reinvent myself. Accordingly, how all these new musical acquaintances found me to be, upon our initial meeting, was to them how I had always been! No questions asked. On 28 July 1989, I had left at Kingsford Smith airport Sydney, a whole load of dreadful baggage: that “ambivalence with being a modern cellist, poor teaching, a lack of down-to-earth guidance, and the sense that I was never going to make it as a modern cellist”. Holland provided me with the golden opportunity to be the musician that I most wanted to be.

And though he was a tough task-master, ultimately for one’s own good, my Dutch teacher Jaap ter Linden was one to take you under his wing and look out for or offer you opportunities that came with his big seal of approval. (Jaap also taught Jenny Eriksson of course. Jenny left Holland the year before I arrived.) You just knew that you had to do the best job you could because Jaap’s reputation, through recommending you, might just be at stake! So, with the good fortune of the benefit of his, as well as other persons of significance having belief in me, I ventured forth as a baroque cellist!

Ultimately, it turned out to be most fortunate that I had so many “votes of confidence” in Europe, as upon returning to Australia, it did not take long for harsh realities to rear their ugly heads. Not only were opportunities to perform lacking, but in many cases, the “dreadful baggage” that I was able to leave behind when I left Australia, was (unbeknownst to me) awaiting my collection upon my arrival home. So, how did that time overseas impact me? It quickly dawned on me that many Australian musicians have rather too-long memories and will never give you the benefit of the doubt.

PP – Can you tell us a little of how and why you came to found your ensemble, Salut! Baroque?

TB – With re-entry to Australia, it was quickly evident to me that if my time away was to be of any long-term meaning, then I had to create my own opportunities. The Australian Brandenburg Orchestra (ABO) was already underway being established in the years that I was in Holland. By returning to Australia, however, I wanted to demonstrate to people the worth of historically-informed performance (HIP). To do so, it seemed to me valid to set up another HIP ensemble. After all, in Holland, there was more than just the Amsterdam Baroque Orchestra (ABO); there were in fact a myriad of orchestras and ensembles all proselytising the good news of HIP.

Initially, with baroque violinist Margaret Caley, I formed the “Ensemble of the Golden Age” (EGA); she and I had been students together in Holland. In turn, she proposed EGA collaborations with a Canberra recorder duo: “Duo Flauto Dolce” – with Sally Melhuish and Robyn Mellor. It is thanks to these early 1990s collaborative projects that Sally Melhuish and I became close friends. In 1995, Sally and I invited harpsichordist Luke Green to join us in establishing Salut! Baroque. The name limited us within the bounds of the baroque period but did not specifying how many players it would entail. In fact, the name is derived from “Sally, Luke & Tim” and means, “Hi!” in French. (Incidentally, my father wished to know why then we didn’t name it “S-lu-t” or “Lu-s-t Baroque”?)

PP – As well as the baroque cello, you also play the bass violin. What is different about the bass violin versus the cello? Do you find it easy to adjust between the two?

TB – The Italian word, “cello”, is not actually a stand-alone word. Rather, it is an adjectival qualifier i.e. it denotes that an object is a small version of the original. Accordingly, when one states to an Italian that one plays the cello, the response is of immediate perplexity and confusion. How is it that one just plays the “small”? That’s not possible; in fact, it’s ridiculous! Rewind a couple of tracks: the full name is actually “Violoncello”. Etymologically, the generic Italian name for any string instrument whatsoever is “Viola” (which did not originally denote the instrument we know today as a 4-string instrument, slightly larger than the violin).

Due to all this etymologising, my curiosity was piqued. I was also captivated by all the still-life paintings, featuring musical instruments, by 17th and early 18th century painters. In these paintings, the large violin family instrument that features are of different proportions to what we now recognise as the “Violoncello”. The width of the top half of the “figure of 8” of the instruments is the same as the bottom half (not so for the Violoncello) and the ribs (sides) are often half as deep again. The neck is relatively chunkier than the Violoncello’s and the feet of the bridge stand wider apart. Often these instruments bear 5 strings, not just 4. So, clearly how these instruments are portrayed demonstrates the proportions as they were originally scientifically determined to support the lower pitches and resonances of these long, thick vibrating strings.

Roughly speaking, the Violoncello is an invention of the last decade of the 17th century, when Tuscan violoncellists coveted emancipation from purely being bassline players and emerge as “virtuosi” or soloists, in their own right – like violinisti. Initially, Violoncelli were Violones – cut down/made small by reducing the width of the top bout and the depth of the ribs (of existing instruments). Accordingly, hybrid instruments were created (yes, the violoncello is a hybrid which scientifically shouldn’t work so well), with a less fundamental timbre but more capable of whizzing about like Violinos, due to the smaller volume of air contained in the resultant soundbox and the thinner gauged strings.

Tuning-wise, the Violone took the lowest Violino “g” string as its point of departure, making that its top “g” string, and descending string by string in 5ths as per the Violino. Hence: g-c-F-Bflat. The Violone, or Bass Violin (England), Basse de Violon (France), Baβ Geige (Germany) remained in vogue the longest in France and England, before being supplanted by the hybrid Violoncello (with the support of the double bass) by mid-18th century. As for the bow, the bow for the Violone/ Basse de Violon is held underhand, as was the case for all string instruments played da gamba. Initially, with tuning just a close Major 2nd lower than the Violoncello, I was doing my head in trying to learn the scale of the Violone. It’s hard not to just think of it as a big Violoncello but to do so only prolongs the confusion and makes swapping from one to the other a very risky business, particularly early on when one is still in the early stages of learning the veritable differences between the two instruments.

Fortunately, with time and experience (now 21 years), to me the Violoncello is definitely one instrument whilst the Violone is definitely another.

PP – The viola da gamba or bass viol, and the bass violin both featured in French baroque era orchestras. Why did the French orchestras of that time use the bass violin rather than the cello?

TB – A violin family set of 38 instruments was ordered by from Andrea Amati by Catherine de Médicis, regent queen of France, bearing hand-painted royal French decorations in gold, including the motto and coat of arms of her son, Charles IX of France (d.1574). Of these 38 instruments ordered, Amati created violins of two sizes, violas of two sizes and violones. With this French violin family came the use, in a way that was entirely new in instrumental music, of the massed “choir” effect in which the several parts were doubled at the unison by like instruments. This string ensemble, so different in its effect from the chamber music of the preceding “golden age,” owes its first organisation, to the French at the court of Louis XIV and Jean-Baptiste Lully, whose vingt-quatre violons du Roi (24 violins of the king) was the model for Europe of the orchestra-to-be.

PP – Tim, thank you so much. We look forward to hearing you on June 17!